Hints for Coaches

Although rules are altered and new techniques are introduced, the basic principles of learning never change. To acquire knowledge or skill the opportunity to practice must be given and this applies to coaches as much as it does to lifters themselves. When stimulated to learn we learn more quickly, so cultivate this trait. When your charges learn effectively, encourage them by showing your approval. Develop an eye for movement so you can correctly evaluate time and distance during a lift. Train yourself to spot where a fault originates rather than where it eventually becomes very obvious. Learn to distinguish from what is cause and what is effect.

Fianlly, and extremely important, gain an appreciation of relative positions of bar and body and feet placings so that you are at all times aware of exactly what is happening. Let us elaborate a little bit.

Very often after a failure, we hear a comment to the effect that the bar was too far forward. More often than not the truth is that the bar was correctly placed over the base, but the body was too far backwards. This is not splitting hairs. If the lifter believed the bar was too far forward and next time pulled it back, he would be in worse trouble, as both bar and body would be too far back. This is only one example of faulty diagnosis during a lift.

A good coach's eye can be a valuable asset but it is again emphasized that to bear out these theories of snatching instead of relying on the naked eye, thousands of feet of film were minutely studied to ascertain the facts given.

We heartily recommend all coaches to study film when possible, not only of the champions but of your own personal charges.

Fianlly, and extremely important, gain an appreciation of relative positions of bar and body and feet placings so that you are at all times aware of exactly what is happening. Let us elaborate a little bit.

Very often after a failure, we hear a comment to the effect that the bar was too far forward. More often than not the truth is that the bar was correctly placed over the base, but the body was too far backwards. This is not splitting hairs. If the lifter believed the bar was too far forward and next time pulled it back, he would be in worse trouble, as both bar and body would be too far back. This is only one example of faulty diagnosis during a lift.

A good coach's eye can be a valuable asset but it is again emphasized that to bear out these theories of snatching instead of relying on the naked eye, thousands of feet of film were minutely studied to ascertain the facts given.

We heartily recommend all coaches to study film when possible, not only of the champions but of your own personal charges.

Movement Patterns of the Champions

First of all we must clarify our aims.

Why should we study the various movement patterns and positions?

We believe this is necessary to give a clear picture of what really happens. So often mental images are completely wrong. You can prove this for yourself by getting a training partner to draw what he thinks is a good position to be in as the bar passes the knees and another of the lowest position in the squat snatch. We are quite sure that the majority will not come very near the positions we describe in this book.

Secondly, there is much to be gleaned from a close study of the methods of the champions especially when we get down to distinguishing between what is cause and what is effect.

Lastly, not until we have at our disposal properly measured information about the extremes as well as the averages, can we base our teachings on fact rather than speculations.

By studying movement patterns of the champions with films, tracings, electromyographs, etc., we can spot significant statistics and find out what is good, what is bad, what is acceptable and what should be avoided.

ALL OUR THEORIES ARE BASED ON THE NATURAL LAW OF GOD. NOT INVENTED BY NEWTON. THESE LAWS ARE HERE TO STAY!

THE RULES OF WEIGHTLIFTING MAY BE ALTERED BUT WHEN THE LAWS OF GRAVITY ARE REPEALED WEIGHT-LIFTERS AND WEIGHT LIFTING WILL BE OBSOLETE!

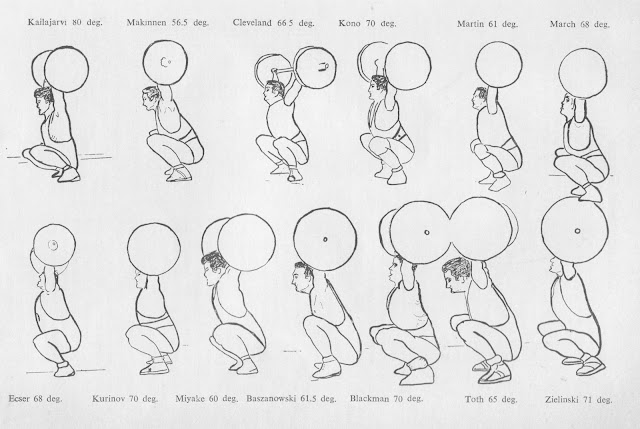

To commence building up movement patterns of the best known lifters, the angle of the back was measured in two positions to discover relative hip and head heights. The first position was as the bar was lifted clear of the floor and the second position was when the bar reached knee height. The angle was measured in relation to the floor.

Measurements of the angles were taken from as near as possible to the 5th cervical vertebrae running down ot the flat part of the sacrum just above the curve of the lifter's buttocks as he lifted the weight. The contours on the back were ignored and if, for example, a lifter rounded his back (e.g. Huska) the line passed right through the curve.

In a study of over 30 top lifters in World Championships, it was found that the angles varied between 8 degrees and 54 degrees as the bar left the floor - a terrific variation, but close scrutiny showed that the majority of the best lifterswere between 16 to 25 degrees. (see fig. 1)

Here is the breakdown of the lifters involved:

On comparing this initial measurement with the position of the back as the bar passed the knees, it was possible to calculate the amount of back movement with the lifters divided into three groups as follows:

Group I

Those whose backs were more vertical as as the bar left the floor than they were as the bar passed the knees, i.e. leg movement without a corresponding back movement thus apparently 'giving to the weight' although the shoulders may indeed have been raised slightly.

Group II

Those who maintained the starting angle until to bar passed the knees, i.e. leg movement only.

Group III

Those whose backs were more horizontal when the bar left the floor than it was as the bar passed the knees.

The following measurements were recorded:

The figures show that Group I start more VERTICAL than average, Makinnen being an exception, but if we eliminate the two Japanese lifters, whose style was definitely unorthodox, we find that they are now more HORIZONTAL than average, as the bar passes the knees.

Group II. This must be the smallest group as it is virtually impossible to lift without changing to some small degree the angle of the back. Their backs tend to be more horizontal than average with the exception of Berger and Lopatin who are more vertical than average. Generally speaking an average group.

Group III. The largest group and large rthan the other two put together. This is the group which used some back movement in addition to leg work to bring the bar to knee height. Most of them start with their backs more horizontal than average as the bar passes the knees.

General:

Group I - 6 squat lifters, 3 split.

Group II - 5 squat lifters, 2 split.

Group III - 9 squat lifters, 9 squat.

Those whose hips are fairly high in the starting position generally used back as well as legs. Although it is difficult and perhaps dangerous to generalize, it seems largely a case of those with a higher starting position use more back work at first. There is no doubt that those with low starting positions use more leg work. It would seem that splitters tend to favor leg and back work slightly more than the squatters, who tend to favor more leg work.

The position of the body as the bar passes the knees is most important and with this in mind, numerous calculations have been made to study this from various points of view. Table 2 shows the "raw" details of different lifters. The average angle of the back in 32 lifts at world championships was 23.6 degrees. This figure however is a trifle misleading and it is more accurate to saythat the standard deviation (calculated mathematically) is 7.07 degrees. In other words, anyone whose back is at an angle of between approximately 17-30 degrees will be in the same range as the majority of top lifters. It is our view that the lower degrees of this range are best for the average person.

It seems likely that the positions adopted depend on the comparative amount of leg and back strength. It could be said that owing to the fact that inertia has to be overcome and body mechanics are less effective, the strongest position should be adopted at the start. However, we do not subscribe to this view. We believe that it is more important that the lifter is in the strongest position as the bar passed the knees or a little later. We would like to see lifters tested in this position to find the exact angle of back and legs at which the maximum force can be applied. This angle could then be noted and if necessary, minor adjustments made to the starting position. Naturally, any alterations made as a result of these tests should keep in mind the overall movement and not just this part of the pull.

In all groups, regardless of the angle of the back, the spine should be extended. If the spine is flexed and during the lift extended against the strong resistance of the bar, the back muscles are less effective and more liable to injury; this is because they are engaged in two conflicting tasks at the same time. They are trying to move the bones of the spine upon each other and at the same time trying to stabilize the back in order that it may act effectively as a lever. Furthermore, with a round back stress is imposed and transmitted through the intervertebral cartilage discs. With a straight back, the main function of the muscles is stability and any stresses are more directly transmitted from bone to bone.

A study of these figures shows that "Classic" positions, generally considered correct, with low hips and upright backs, are not always adopted by the champions of 1961064. There is also less movement of the back in the early part of the movement than many people imagine.

Table 3 shows that in the vast majority of lifters there is less than 5 degrees alteration to the angle of the back. We believe that it is best to maintain the starting angle of the back or increazse the angle slightly rather than make the angle more acute.

Summation of Forces

Measurements of the angles were taken from as near as possible to the 5th cervical vertebrae running down ot the flat part of the sacrum just above the curve of the lifter's buttocks as he lifted the weight. The contours on the back were ignored and if, for example, a lifter rounded his back (e.g. Huska) the line passed right through the curve.

In a study of over 30 top lifters in World Championships, it was found that the angles varied between 8 degrees and 54 degrees as the bar left the floor - a terrific variation, but close scrutiny showed that the majority of the best lifterswere between 16 to 25 degrees. (see fig. 1)

Here is the breakdown of the lifters involved:

On comparing this initial measurement with the position of the back as the bar passed the knees, it was possible to calculate the amount of back movement with the lifters divided into three groups as follows:

Group I

Those whose backs were more vertical as as the bar left the floor than they were as the bar passed the knees, i.e. leg movement without a corresponding back movement thus apparently 'giving to the weight' although the shoulders may indeed have been raised slightly.

Group II

Those who maintained the starting angle until to bar passed the knees, i.e. leg movement only.

Group III

Those whose backs were more horizontal when the bar left the floor than it was as the bar passed the knees.

The following measurements were recorded:

The figures show that Group I start more VERTICAL than average, Makinnen being an exception, but if we eliminate the two Japanese lifters, whose style was definitely unorthodox, we find that they are now more HORIZONTAL than average, as the bar passes the knees.

Group II. This must be the smallest group as it is virtually impossible to lift without changing to some small degree the angle of the back. Their backs tend to be more horizontal than average with the exception of Berger and Lopatin who are more vertical than average. Generally speaking an average group.

Group III. The largest group and large rthan the other two put together. This is the group which used some back movement in addition to leg work to bring the bar to knee height. Most of them start with their backs more horizontal than average as the bar passes the knees.

General:

Group I - 6 squat lifters, 3 split.

Group II - 5 squat lifters, 2 split.

Group III - 9 squat lifters, 9 squat.

Those whose hips are fairly high in the starting position generally used back as well as legs. Although it is difficult and perhaps dangerous to generalize, it seems largely a case of those with a higher starting position use more back work at first. There is no doubt that those with low starting positions use more leg work. It would seem that splitters tend to favor leg and back work slightly more than the squatters, who tend to favor more leg work.

The position of the body as the bar passes the knees is most important and with this in mind, numerous calculations have been made to study this from various points of view. Table 2 shows the "raw" details of different lifters. The average angle of the back in 32 lifts at world championships was 23.6 degrees. This figure however is a trifle misleading and it is more accurate to saythat the standard deviation (calculated mathematically) is 7.07 degrees. In other words, anyone whose back is at an angle of between approximately 17-30 degrees will be in the same range as the majority of top lifters. It is our view that the lower degrees of this range are best for the average person.

It seems likely that the positions adopted depend on the comparative amount of leg and back strength. It could be said that owing to the fact that inertia has to be overcome and body mechanics are less effective, the strongest position should be adopted at the start. However, we do not subscribe to this view. We believe that it is more important that the lifter is in the strongest position as the bar passed the knees or a little later. We would like to see lifters tested in this position to find the exact angle of back and legs at which the maximum force can be applied. This angle could then be noted and if necessary, minor adjustments made to the starting position. Naturally, any alterations made as a result of these tests should keep in mind the overall movement and not just this part of the pull.

In all groups, regardless of the angle of the back, the spine should be extended. If the spine is flexed and during the lift extended against the strong resistance of the bar, the back muscles are less effective and more liable to injury; this is because they are engaged in two conflicting tasks at the same time. They are trying to move the bones of the spine upon each other and at the same time trying to stabilize the back in order that it may act effectively as a lever. Furthermore, with a round back stress is imposed and transmitted through the intervertebral cartilage discs. With a straight back, the main function of the muscles is stability and any stresses are more directly transmitted from bone to bone.

A study of these figures shows that "Classic" positions, generally considered correct, with low hips and upright backs, are not always adopted by the champions of 1961064. There is also less movement of the back in the early part of the movement than many people imagine.

Table 3 shows that in the vast majority of lifters there is less than 5 degrees alteration to the angle of the back. We believe that it is best to maintain the starting angle of the back or increazse the angle slightly rather than make the angle more acute.

Summation of Forces

There are many different ways of pulling.

In the pull some lifters use mostly legs, other mostly back. Some use legs first, back later, others the opposite. Some try to share the load evenly.

Theoretically, it does not matter in which order the muscles are used providing they are all worked to the maximum. In practice, however, several points must be carefully watched. Different body parts have different weights, strength and speed. It is suggested that in weight-lifting, as in other heavy athletics, the stronger, slower body parts should be used first (hips, legs and back) and the weaker, faster parts later (calves, shoulders, arms and wrists). The movments in this summation of forces should be linked so there is a smooth and overlapping changeover, e.g. the arms and shoulders should come into play JUST BEFORE the final extension. The common and comparatively unpublicized fault is the overuse of the legs while the angle of the back is reduced during the first part of the pull.This reduces the angular momentum of the back. The aim should be maximum acceleration of the bar as the feet are leaving the floor.

We have advised that the arms be brought into play just before complete extension and because the fully extended position is one of the "key positions" it is necessary to give some guidance as to how much the arms should be bent at this stage. Here is a simple and accurate method to ascertain the position we advocate.

Stand erect and mark on the gym wall the height of the center of your belt. Make another mark 3-4" above this. Now grasp the bar in your normal snatch grip and standing erect bend the arms till the bar is at a height between the two marks.

This will show you the amount of arm bend you require at this stage and incidentally also shows the approximate height the bar should be at before you begin the split or squat.

This procedure is suggested after study of the top lifters filmed at the World Championships in Stockholm, 1963. This survey showed that the champion lifters pulled the bar to around 103% of standing belt height before going under the bar.

The lifter's standing belt-height was measured when the bar was held overhead at the completion of the lift. This figure was taken as 100%.

Column 1 shows the height to which the bar was pulled before the lifter started to go under the weight. This is expressed as a percentage of the standing belt-height.

Column 2 shows the height of the bar in the lowest position off the lifter under the bar either squatting of splitting. This too is noted as a percentage of standing bar-height.

It is interesting to note that in the low position of the lifts most pleasing coach's eye were those of Nagy and Martin. Column 2 shows these to be the two lowest positions. The other two Hungarians (Veres and Huska) however were splitters and did not go nearly so low.

In the low position the average height of the bar is lower with squat lifters than with those who split.

Next: Maximum Extension

This will show you the amount of arm bend you require at this stage and incidentally also shows the approximate height the bar should be at before you begin the split or squat.

This procedure is suggested after study of the top lifters filmed at the World Championships in Stockholm, 1963. This survey showed that the champion lifters pulled the bar to around 103% of standing belt height before going under the bar.

Table 4

The lifter's standing belt-height was measured when the bar was held overhead at the completion of the lift. This figure was taken as 100%.

Column 1 shows the height to which the bar was pulled before the lifter started to go under the weight. This is expressed as a percentage of the standing belt-height.

Column 2 shows the height of the bar in the lowest position off the lifter under the bar either squatting of splitting. This too is noted as a percentage of standing bar-height.

It is interesting to note that in the low position of the lifts most pleasing coach's eye were those of Nagy and Martin. Column 2 shows these to be the two lowest positions. The other two Hungarians (Veres and Huska) however were splitters and did not go nearly so low.

In the low position the average height of the bar is lower with squat lifters than with those who split.

Next: Maximum Extension

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий