Today’s Thursday Throwback is one of my most popular posts ever. This post gained traction quickly as it discusses the largest underlying factor in why so many athletes and lifters alike get shoulder pain while benching and doing other pressing exercises.

Since this post was first published over 3 years ago, I’ve continued to emphasize the importance of having some sort of screen to pre-qualify yourself (or your athletes) for specific exercises, and the necessity of having a system to make program changes if a specific exercise is not a good fit for an athlete. This is the system I use at Endeavor: Optimizing Movement

Enjoy the post and if you know anyone that has experienced shoulder pain while benching or doing push-ups, please share this with them!

Last week I got an email from my step sister saying that she’s been getting shoulder pain during bench pressing and dumbbell raising exercises. I had a similar conversation with a hockey parent a week before about one of his son’s teammates. In both cases, it’d be impossible for me to say with 100% confidence that I know exactly why they’re in pain and what they can do to fix it. As you know, non-traumatic pain tends to be multi-factorial and necessitates considerations to static and dynamic postures. In other words, how we hold ourselves throughout the day and how we move plays a large role in soft-tissue overload.

With that said, I’d bet my car (an estimated value of $137), that in both of these cases, the bench press is performed with a similar fault – the elbows are out too wide. Let’s walk through this:

It’s somewhat hard to tell from this picture, but my elbows are approaching 90 degrees off my side. In other words, my upper arm and the side of my rib cage form about a 90 degree angle. This puts a tremendous amount of stress on the anterior shoulder capsule at the bottom of the lift. It also increases the risk of having the glenohumeral head impinging on the structures superior to it.

It’s somewhat hard to tell from this picture, but my elbows are approaching 90 degrees off my side. In other words, my upper arm and the side of my rib cage form about a 90 degree angle. This puts a tremendous amount of stress on the anterior shoulder capsule at the bottom of the lift. It also increases the risk of having the glenohumeral head impinging on the structures superior to it.

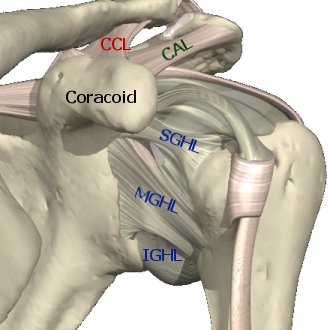

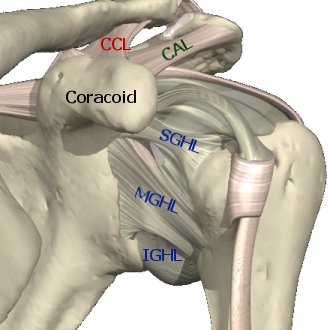

Ligaments of the shoulder

The picture above illustrates the ligaments of the shoulder. As you approach the bottom of a bench press with your elbows flared out, it tends to put excessive stretch on the IGHL and MGHL ligaments displayed above and increases the chances of impinging the ligaments and tendons between the acromion and glenohumeral head (long head of biceps brachii tendon and subacromial bursa are two notables).

The same is true for push-ups, although there tend to be some other differences between bench pressing and doing push-ups. For instance, push-ups allow free movement of the scapulae, allowing the shoulder a bit more freedom than during bench pressing, which may delay the onset of pain from resulting from the elbows being out too wide. Of course, because your body isn’t supported by a bench during a push-up, it also means more freedom of movement for other joints; as a result, it’s common to see people with sagging hips, excessively arching backs and protruding chins (or what I call “bird neck syndrome” or BNS).

Ligaments of the shoulder

The picture above illustrates the ligaments of the shoulder. As you approach the bottom of a bench press with your elbows flared out, it tends to put excessive stretch on the IGHL and MGHL ligaments displayed above and increases the chances of impinging the ligaments and tendons between the acromion and glenohumeral head (long head of biceps brachii tendon and subacromial bursa are two notables).

The same is true for push-ups, although there tend to be some other differences between bench pressing and doing push-ups. For instance, push-ups allow free movement of the scapulae, allowing the shoulder a bit more freedom than during bench pressing, which may delay the onset of pain from resulting from the elbows being out too wide. Of course, because your body isn’t supported by a bench during a push-up, it also means more freedom of movement for other joints; as a result, it’s common to see people with sagging hips, excessively arching backs and protruding chins (or what I call “bird neck syndrome” or BNS).

Brutal Push-Up…but decent display of BNS

In both exercises, the goal is to keep the elbows within 45 degrees off the side of the body and to retract the scapulae (squeeze the shoulder blades back and down) as you go down. Because the scapulae aren’t free to move during a bench press, it’s important to set up on the bench with your scapulae in the correct position, packed back and down, and to keep them there throughout the movement.

Brutal Push-Up…but decent display of BNS

In both exercises, the goal is to keep the elbows within 45 degrees off the side of the body and to retract the scapulae (squeeze the shoulder blades back and down) as you go down. Because the scapulae aren’t free to move during a bench press, it’s important to set up on the bench with your scapulae in the correct position, packed back and down, and to keep them there throughout the movement.

Bench Press with correct positioning

With push-ups, the shoulder blades aren’t wedged between your rib cage and the bench so they can move freely. When going down in a push-up, think of pulling your chest down to the floor and pulling your shoulder blades back and down along the way.

Bench Press with correct positioning

With push-ups, the shoulder blades aren’t wedged between your rib cage and the bench so they can move freely. When going down in a push-up, think of pulling your chest down to the floor and pulling your shoulder blades back and down along the way.

Push-Up with proper technique. Notice how the hands are beneath the shoulders, the elbows are within 45 degrees of the sides of the body and the chin is tucked back.

If you already have shoulder pain, it may be best to back off the pressing exercises for a week or two and focus more on rowing exercises, emphasizing pulling the shoulder blades back and down as you pull the weight toward your chest. If it’s not that bad, the floor press is a great exercise to reteach a proper pressing pattern while limiting the stress on the shoulder because of the decrease in range of motion.

Push-Up with proper technique. Notice how the hands are beneath the shoulders, the elbows are within 45 degrees of the sides of the body and the chin is tucked back.

If you already have shoulder pain, it may be best to back off the pressing exercises for a week or two and focus more on rowing exercises, emphasizing pulling the shoulder blades back and down as you pull the weight toward your chest. If it’s not that bad, the floor press is a great exercise to reteach a proper pressing pattern while limiting the stress on the shoulder because of the decrease in range of motion.

Dumbbell Floor Press

With regards to push-ups, I think most of the problem comes from people assuming they can do push-ups on the ground right away. This stems back to an interesting paradox in youth training, where there is still the perception that lifting weights is dangerous but people are free to do as many push-ups as they want. In reality, I’ve come across very few athletes 14 and under that can do a single push-up the correct way on the floor. As with any exercise, it’s important to progress the loading as the individual develops the strength to perform it correctly. In this case, the overwhelming majority of people need to start performing push-ups on an inclined surface and focus on proper body positioning and proper movement (e.g. moving as a unit connected from ears to ankles, descending so that the lower chest is the first region to touch the ground or raised implement and keeping the elbows within 45 degrees of the side). As people progress in strength, you simply lower the implement closer and closer to the ground.

At Endeavor, we use the safety bars in our squat racks to accomplish this. This way it’s easy for us to objectively assess progress as each level is numbered. As the athlete gets stronger, they approach higher and higher numbers as the bar lowers closer to the ground.

Dumbbell Floor Press

With regards to push-ups, I think most of the problem comes from people assuming they can do push-ups on the ground right away. This stems back to an interesting paradox in youth training, where there is still the perception that lifting weights is dangerous but people are free to do as many push-ups as they want. In reality, I’ve come across very few athletes 14 and under that can do a single push-up the correct way on the floor. As with any exercise, it’s important to progress the loading as the individual develops the strength to perform it correctly. In this case, the overwhelming majority of people need to start performing push-ups on an inclined surface and focus on proper body positioning and proper movement (e.g. moving as a unit connected from ears to ankles, descending so that the lower chest is the first region to touch the ground or raised implement and keeping the elbows within 45 degrees of the side). As people progress in strength, you simply lower the implement closer and closer to the ground.

At Endeavor, we use the safety bars in our squat racks to accomplish this. This way it’s easy for us to objectively assess progress as each level is numbered. As the athlete gets stronger, they approach higher and higher numbers as the bar lowers closer to the ground.

Incline Push-Up

Incline Push-Up

In a team off-ice training setting (especially with younger teams), this can be tough. In these situations, I’m more apt to use our jump boxes, which are set at heights of 24, 18, and 12 inches. Using these, I can start everyone at the top box and progress them lower on an individual basis as they demonstrate sufficient strength. If someone mastered the 18″ box, but isn’t quite ready for the 12″, you can just lengthen the negative or “going down” phase of every rep to make it a bit tougher.

Pressing movements are an essential part of any person’s training program. Unfortunately, they’re also one of the most common causes of upper body pain. Making the simple corrections discussed above will help make you stronger than ever, while keeping you pain free!

To your success,

Kevin Neeld

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий