July 14, 2013

By Jim Bathurst

For athletes looking to get their first muscle-up – whether on the rings or the bar – who may have tried and failed numerous times. You may have studied videos, read progressions, been thoroughly coached and yet still the skill remains elusive. This article is for you.

For the coach who just can’t seem to understand why their athlete can’t get the muscle-up. You may have analyzed every bit and piece of their technique, yet something is still missing. This article is for you.

I’ve traveled to numerous CrossFit facilities over the past several years. I’ve been asked to teach the athletes various gymnastic skills, one of the most highly requested being the muscle-up. I have seen countless athletes try and fail and I have seen the same athletes try again with my coaching and succeed.

While it does not take athletes long to grasp the basic concept of a muscle-up, a chin-up that transitions into a dip, it’s the finer points that make the difference between success and failure; or even just a strong muscle-up from a weak one. Let’s look at some of those points.

Image 1

WRONG: Hand is in the center, wrist is off-center

WRONG: Hand is in the center, wrist is off-center

Image 2

Right: Wrist is in the center, hand is off-center

Right: Wrist is in the center, hand is off-center

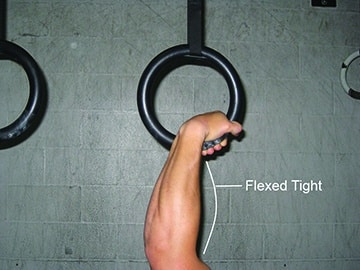

False Grip: Where’s Your Wrist

While learning a muscle-up with a false grip can be frustrating, the advantage this grip gives is too good to pass up. It gives you a head start for the transition. Setting the false grip correctly will allow for a strong pull to get over the rings.

If you take a look at the ring, you can imagine it like a clock face with the strap at 12 o’clock on the dial. Too often I see athletes put their hand at 6 o’clock on the dial with their goose-necked wrist. (Image 1)

While learning a muscle-up with a false grip can be frustrating, the advantage this grip gives is too good to pass up. It gives you a head start for the transition. Setting the false grip correctly will allow for a strong pull to get over the rings.

If you take a look at the ring, you can imagine it like a clock face with the strap at 12 o’clock on the dial. Too often I see athletes put their hand at 6 o’clock on the dial with their goose-necked wrist. (Image 1)

While at first this seems like a normal false grip, it will in fact prove weak when pulled strongly upon. The load bearing point for the false grip is closer to the wrist than the palm of the hand. Therefore, the wrist needs to sit at 6 o’clock on the ring, not the palm of your hand. (Image 2)

A quick pull on the rings with this latter grip should prove stronger than the former one.

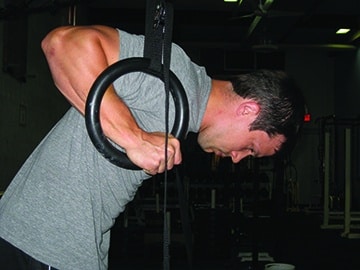

Learn to Relax

While we’re talking about the wrist, let’s discuss which muscles of the lower arm should be engaged when preparing for a muscle-up.

While we’re talking about the wrist, let’s discuss which muscles of the lower arm should be engaged when preparing for a muscle-up.

Image 3

Forearm is tight. Hand is loose.

Forearm is tight. Hand is loose.

When your hands are wrapped around the rings or a bar, you may naturally want to squeeze everything to death. If you do this, you’ll lose focus on the real muscles that should be working – the forearms. You can actually hold your grip a bit looser than you’d expect, so that your forearm can flex tighter and keep the false grip set securely. This is in the case of the ring muscle-up. In the case of the bar muscle-up with no false grip, keep a looser grip so that your hand can spin around the bar and your wrists can turn over top of the bar more easily.

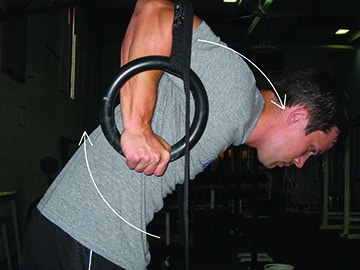

Use Your Head

I often equate the muscle-up to climbing up on top of a wall. If you imagine those playground days of climbing, you’ll remember that when you got to the top of the wall, you threw your bodyweight forward. You needed to get your head and shoulders forward, or you would fall backwards off the wall. The same concept applies to the muscle-up.

I often equate the muscle-up to climbing up on top of a wall. If you imagine those playground days of climbing, you’ll remember that when you got to the top of the wall, you threw your bodyweight forward. You needed to get your head and shoulders forward, or you would fall backwards off the wall. The same concept applies to the muscle-up.

First, as touched upon in the last section, your wrists need to get above the rings or bar. This is the advantage of the false grip – it already puts your wrists where they need to be. If you do a muscle-up without a false grip, then you’re taxed with having to turn your wrists over quickly enough to support and push your weight. The wrists turn over quickly when you get your head and shoulders forward quickly at the top.

Image 4

Forearms are not perpendicular to the ground.

Forearms are not perpendicular to the ground.

On both the bar and the rings, with your wrists over top the apparatus, the next thing in line needs to be your forearms. If your forearms are not perpendicular to the ground, you will fall backward. (Image 4) I see this point overlooked on the rings most often.

When watching an athlete from the side, you can determine if they’ve gotten their head and shoulders forward enough by whether their forearm is perpendicular. Some will keep their head and gaze up too high, and not “turn over” the rings enough.

Image 5

Pull the rings back. Push the head and shoulders forward. Forearms perpendicular to the ground.

Pull the rings back. Push the head and shoulders forward. Forearms perpendicular to the ground.

When done correctly, the pull of the rings and the push forward of the head and shoulders will create a circular movement in order to get the athlete into their dip. (Image )

Watch an athlete’s forearms to determine whether they’ve got themselves far enough over. Some will simply hold back the turn over for fear of going too far and falling through the rings.

Watch an athlete’s forearms to determine whether they’ve got themselves far enough over. Some will simply hold back the turn over for fear of going too far and falling through the rings.

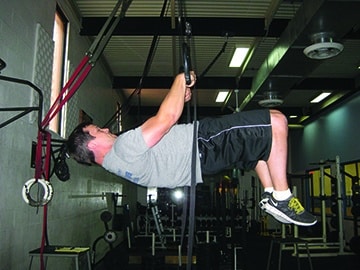

Use Your Legs

This is one of the major differences between my muscle-up progression and the progressions I’ve seen at other gyms. While the technique I’m about to lay down is quite well known in the gymnastics world (it’s called a front uprise), it seems relatively unknown in our community. It is so powerful though, that it often results in athletes getting their first muscle-up at my seminar.

This is one of the major differences between my muscle-up progression and the progressions I’ve seen at other gyms. While the technique I’m about to lay down is quite well known in the gymnastics world (it’s called a front uprise), it seems relatively unknown in our community. It is so powerful though, that it often results in athletes getting their first muscle-up at my seminar.

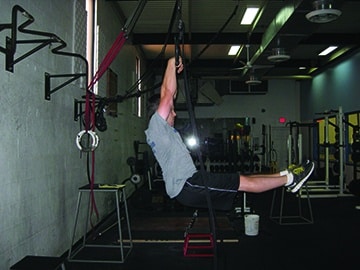

Image 6

WRONG: Body directly under the rings

WRONG: Body directly under the rings

When using the legs to assist in the muscle-up, many will approach the skill like a kipping pull-up. That is, they will swing their legs back and forth and after they’ve swung their legs to the front, they then violently explode the hips open to raise their body to the rings.Unfortunately, when they do this they put their body directly underneath the rings. (Image 6)

If we remember the wall analogy, we want to go over the top of the wall. By kipping, we put ourselves underneath it – the exact place we don’t want to be! Many get stuck here and are unable to complete the muscle-up. Those that do succeed with their muscle-up, I would argue, are doing so very inefficiently.

Image 7

Shoulders engaged. Torso Upright. Swinging legs forward

Shoulders engaged. Torso Upright. Swinging legs forward

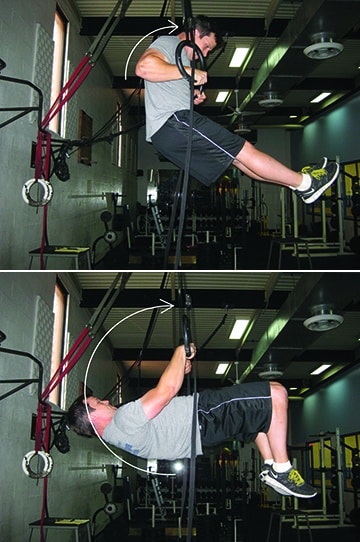

However, what is criticism without an alternative? Instead of violently exploding the hips open, I prefer to swing my legs upward and keep my hips closed – as if I’m swinging my legs into an L-sit pull-up. My torso remains relatively upright, instead of laying back. (Image 7)

By timing the swing of my legs with the pull of my arms, I not only assist in the muscle-up, but I also keep my body behind the rings. Completing the muscle-up is then a matter of moving my head and shoulders around 1/4 of a circle, instead of the 1/2 circle that the kipping muscle-up requires. (Images 8 and 9)

Images 8 & 9

Efficient 1/4 turn vs. inefficient 1/2 turn.

Efficient 1/4 turn vs. inefficient 1/2 turn.

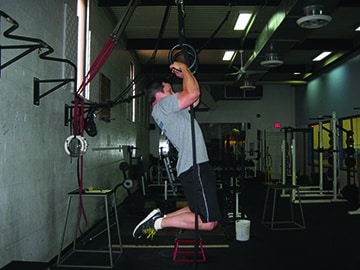

Applying that same concept of a leg swing and upright torso, I can perform a muscle-up over a bar. (Image 12)

The kipping technique for the muscle-up is adopted from the kipping pull-up technique. In that skill, we look to reach the bar. When you want to get over the bar, try the L-sit swing instead.

Shoulder and Wrist Strength

I believe every serious athlete should be able to do a strict muscle-up. It is a display of scapular strength and control and a basic staple in gymnastics training. Even if the athlete performs leg-assisted muscle-ups in competition or training, the strength required for strict muscle-ups will allow the athlete to perform more assisted ones.

That said, I understand that many get their first muscle-up with a leg assist. For those using their legs, they may be encumbered by something other than their technique. Lack of basic strength in the shoulders and wrists makes itself very apparent when attempting muscle-ups.

Image 10

Shoulders too high. Elbows should be closer to locked out.

Shoulders too high. Elbows should be closer to locked out.

When people hang from the rings and start swinging their legs, it is very common to see the athlete’s elbows bend up to 90 degrees. Their shoulders oftentimes come up around their ears. (Image 10)

This position makes it difficult to swing the legs properly, not to mention it would never pass in a CrossFit competition – as rings/knuckles often have to be turned out at the bottom.

What is causing this problem? Oftentimes a combination of weakness in the shoulders and wrists.

Image 11

Shoulder back and down. Chest touching the bar. No leg help.

Shoulder back and down. Chest touching the bar. No leg help.

To determine if it is shoulder weakness, look at the athlete’s chin-up and pull-up on a regular bar. Are they able to keep their shoulders back and down? Are they able to pull themselves up so that their chest touches the bar, without forward movement of the knees? This is not as easy as it sounds. Getting this strict chest to bar pull-up is a prerequisite for a strict muscle-up and getting close to this standard displays the necessary scapular strength for a leg-assisted muscle-up. (Image 11)

If shoulder strength is adequate, based on the above, then we can determine that it is likely weakness in the athlete’s false grip that is holding them back. Athletes will compensate for a poor false grip by inappropriately bending the arms during the swing. This is because it gives them greater leverage on the false grip by essentially wrapping the wrist over top the ring further than it would normally be.

If you find it’s your false grip, drill false grip hangs in order to strengthen the position. With the rings up high, stand on a box, establish the false grip, pull your shoulders down and back into the proper position and slowly start to remove your weight from the box. You may not remove your feet completely during the first session, but gradually you’ll remove weight until you’re hanging strongly from the false grip.

Lastly, let’s discuss chin-up strength. If you are unable to perform a strong, fast chin-up (and I mean fast), then time is much better spent strengthening that skill than working on the muscle-up. The muscle-up is a sexier skill, but it is made up of foundational skills. Building a stronger foundation, a better chin-up and a stronger false grip, will solve many problems. If your foundation is strong, and you’ve made countless attempts, then it’s time to read this article again. Good luck!

Here’s Jim tackling some strict weighted muscle-ups:

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий