One of the most persistent myths in the entire panoply of conventional exercise wisdom is that squats below parallel are somehow bad for the knees. This old saw is mindlessly repeated by poorly-informed orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, and chiropractors all over the world. Better-informed professionals such as productive strength coaches, weightlifters and powerlifters, and those willing to examine the anatomy of the knees and hips for more than just a minute or two, know better. Here are four reasons why.

1. The below-parallel (hips just below the knees) squat position is a perfectly natural position for the human body. People all over the non-air-conditioned world spend time squatting as a resting position throughout the day, and all of them arise from it without injury. There is nothing harmful about either assuming a squatting position -- whether sitting down in a chair or into an unsupported squat -- or returning to a standing position afterwards. The world record for the squat in the sport of powerlifting is now over 1,000 pounds, and the guy is just fine.

We've been squatting since we've had knees and hips, and certainly since the development of the toilet. The relatively recent idea of gradually loading this natural movement with a barbell doesn't change the fact that it will not hurt you. If you do it correctly -- you don't get to do the squat wrong and then claim that squatting hurts your knees, any more than you get to drive your car into a bridge and then say that cars are dangerous.

This discussion refers specifically to the strength training version of the movement, the one designed to make you progressively stronger by lifting progressively heavier weights. If you are doing squats as calisthenics, it doesn't much matter how you do your hundreds of reps, because you're going to get sore knees anyway.

2. The reason a weighted squat using sets of five reps doesn't hurt your knees is that a correctly-performed full squat is not really a knees-dependent movement. The squat is a hips movement. The knees just go along for the ride; if you squat down, your knees have to bend, but they don't have to take the majority of the stress. The hips are much better protected joints than the knees. They are completely surrounded by muscle -- muscle that rapidly adapts to the stress of squatting by getting stronger and better at squatting. The correct squat drives the hips back and the knees out to the side a little during the descent. This puts the majority of the force on the hips where it belongs.

The squat is also a back exercise, because it is best performed with a more horizontal back angle than is typically recognized as correct by less-experienced exercise trainers. This back angle allows the bar to stay over the middle of the foot -- the body's natural center of balance against the floor. And the more-horizontal back position allows the hips to do their part of the work, keeping the stress off the knees and providing a way to progressively strengthen the back too.

But more specifically, the full squat is not only safe for the knees, it strengthens the muscles that operate and protect the knees so effectively that nothing else even compares to it as a basic exercise for the lower body.

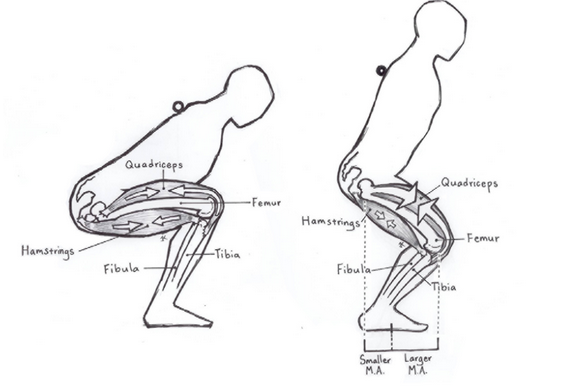

The quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh attach to the tibia (the shin bone) just below the kneecap, on the bump at the top of the bone on the front. When they pull on the knee, the force is directed forward relative to the knee joint. Balancing this forward force is the backward pull from the hamstrings, which attach on either side of the same bone (the top of the tibia). When the hamstrings are positioned correctly by the hips moving back and the torso leaning forward, the backward pull from the hamstrings balances the forward pull from the quads. This balance is optimum when the hips drop just below the level of the knees.

3. The advice to never allow the knees to bend past 90 degrees, or to never go below parallel, ignores the fact that the squat is not merely a way to "do quads." The full squat works all of the muscle mass in the body below the position of the bar on the shoulders. To maximize the amount of muscle worked, the squat must be done slightly below parallel with the knees out, the back angle in a position to keep the bar balanced over the middle of the foot, the neck in a neutral position, and the hips bearing most of the load. This correct version of the squat works all the hip muscles, all the leg muscles, all the back and abdominal muscles, and protects the knees, the spine, and the neck while allowing progressively heavier weights to be lifted.

4. Partial squats have a marked tendency to leave the hamstrings -- and their important backward-directed tension that protects the knees -- out of the movement. This is because partial squats are so often performed with a more vertical back, either accidentally or due to poor instruction.

A partial squat also allows the use of much heavier weights, because you don't have to move them as far. Unsupervised kids in the gym do this all the time. Unfortunately, so do high school football players under the often less-than-qualified guidance of their coaches. After all, it's very cool if your entire defensive line is "squatting" 500 pounds. As a general rule, if the bar is so heavy that you cannot squat below parallel with it and stand back up, it's too heavy to have on your back.

The below-parallel squat is the best exercise in the entire catalog for whole-body strength, power, balance, coordination, bone density, joint integrity, and mental toughness -- good things to develop if you don't have them. Learn to do them correctly, start out light and go up in weight a little each workout, and watch the improvement happen faster than it ever has before.

Mark Rippetoe is a powerlifter, trainer, coach and author of Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий