Part I went over the benefits and disadvantages of the deep squat. In Part II, I will describe how I approach the squat in different settings and how I train it. Contrary to Part I, which was a collection of the current research and physiological facts about the squat, Part II is mostly empirical evidence and professional opinion.

In the Clinic

Is the Deep Squat a Physical Therapy Intervention?

As movement therapists, should we have people deep squatting as an exercise?

The answer is that it all depends on your priorities and the patient’s limitations.

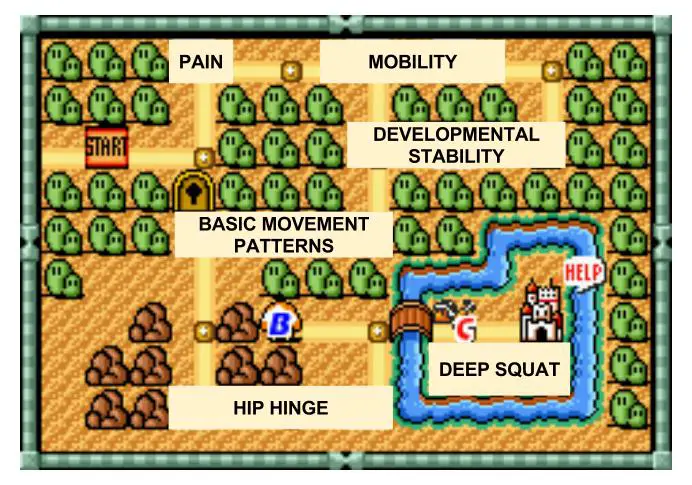

If someone is in physical therapy for pain, they will likely have many other impairments and dysfunctions that need to be corrected first. The deep squat might be pretty far down the line for them. Why?

The deep squat is a high level, complicated movement. It has many parts coming together for a complex movement pattern. Most patients I see are not ready to perform this movement as an exercise. They need a lot work on the “parts” just to get to be able to perform a clean unloaded deep squat. As a result, you may need to master more primitive movement patterns before you attempt the deep squat.

Which Patients Should Deep Squat?

Squat On

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that the Deep Squat doesn’t belong in rehab. In fact, I think there are many patients that can benefit from this exercise while in physical therapy.

If the deep squat correlates with their injury, impairments, movement deficits, goals, and lifestyle, then the deep squat should be a focus. For example, if someone comes in with lateral knee pain, weak quads, and needs to squat down to play with their kids, then the deep squat might be a great exercise (eventually). If someone comes in with weak glutes, valgus moment at the knee, and likes to play squash, then the deep squat might be a great exercise to work on.

Think Twice Before Deep Squatting

More times than not, the patient is so far away from a deep squat that it would take longer than the average bout of physical therapy to get them to where they need to be. For example, if someone comes in with back pain and can’t touch their toes, brace their abdominals, or hip hinge, then the deep squat is not a priority.

If someone has a structural pathology that cannot be changed (eg hip OA, bone spurs, meniscus pathology), then the deep squat may never be part of their program. For example, if someone comes in with chronic knee pain, meniscus pathology, and a hip impingement, then the deep squat is not a good exercise for them.

Now I’m not saying that these patients should never squat. Many of these patients can eventually learn to squat. But when they walk into the clinic, there are usually many other variables that need to be addressed first.

Keep in mind that as physical therapists our goal is to decrease the patient’s pain and help them move better; not to force the most complicated movement pattern on them to perfection.

In the Gym

It’s not much different in the gym than in the clinic; priorities and limitations are still the name of the game.

Not Everyone Wants to Deep Squat

Some people may not be in the best position to deep squat and would need a lot of work to gain this ability. Plus, you have to respect the fact that some people have different priorities. Some people don’t want to spend the necessary time to improve their movement patterns. Some just want to get their heart rate up and sweat. Forcing the deep squat on someone who won’t put in the work to improve their movement quality is dangerous.

Building a Better Athlete

However, if your client is in the gym because they want to get stronger, move better, and improve performance, then the deep squat needs to be a goal and trained consistently. The abundance of benefitsfrom the deep squat are just too good to pass up. Simply put, if you’re not squatting, you are missing out on some major strength, stability, and mobility gains.

Not only does it generate strength and mobility, but many consider the squat as one of the most important strength and conditioning movements (others: push, pull, hinge, loaded carry). Missing out on one of the most fundamental exercises is a recipe for disaster and will handicap anyone’s athletic development.

From a movement pattern perspective, the deep squat has a big carry-over to many other movements. Much like how a solid deadlift sets a great foundation for kettlebells and horizontal force development, the deep squat sets a great foundation for the olympic lifts and vertical force development.

Going beyond the weight room, the squat also prepares athletes for what Charlie Weingroff has termed “level changing”. The ability to vertically change your center of mass (COM) in relation to gravity is what the squat is all about. Athletes are forced to do this over and over in their sports. The defensive end has to go from low to high and explode off the blocks, the squash player has to go from high to low to get to that drop shot, the basketball player has to from low to high when attempting to block a shot. If the athlete is inefficient and doesn’t have adequate vertical real estate to perform these movements, they’ll have to compensate and waste valuable energy.

Prerequisite to Train the Squat

Mobility

There are many prerequisites before someone can begin to work on the deep squat. The most important prerequisite is to have adequate mobility to achieve the bottom position without compensations.

For some, this may take a long time to correct before they can start to deep squat. Others may only need a few weeks to clean up some restricted areas. A big part of this is going to depend on their genetics, development, history, and whether it’s more of a structural adaptation or a neurological phenomenon.

The 4 main areas you need to focus on are

- Ankle Mobility

- Knee Mobility (rarely needs work)

- Hip Mobility

- Thoracic Mobility

As always, there are many different ways to achieve the same result. First assess and find the specific local impairment. Then use whatever you’re good at to help the patient achieve the necessary mobility to squat cleanly.

Training the Squat

One of the best things I’ve learned from Gray Cook is the importance of movement patterns. It’s often not a strength or mobility issue; it’s a neurological movement pattern issue.

With that in mind, you want to start training the movement patterns in the right level of challenge. If it’s too difficult, they won’t be able to adapt to the movement. If it’s too easy, they won’t be challenged enough to improve the pattern.

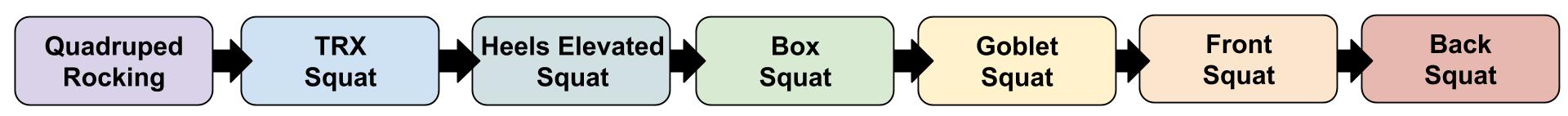

As a PT, I sometimes see people that need to start from ground the ground up, literally…from the ground. Below is a progression I often use with people. The prerequisite before each exercise is proficiency in the one before it. However, this isn’t set in stone, it’s just an example. The progression should vary per individual, but the concepts should remain the same (unloaded before loaded, assisted before unassisted, etc.)

Another important part of training the squat is to make sure you have clean movement before you add a load. If you load up a compensated pattern, you will be reinforcing that faulty movement pattern. You will be “saving” the compensation. And this “saved” movement pattern can come out at a time when it can seriously damage the athlete. This is one of the reasons why many need to “maintain the squat, train the deadlift” (another Gray Cookism).

So if the movement pattern needs work, don’t load it up. But once they’ve got the movement pattern down, feel free to load it up with the goblet squat, front squat, and/or back squat.

Quadruped Rocking

Quadruped rocking is a great place to start for 2 reasons.

One, it provides a movement that unloads spine, hip, knee, and ankle joint. It also allows the patient to “grease the groove” of lumbar/hip dissociation. Thus, it can be a great starting point to train neutral spine.

Two, as Stuart McGill has pointed out, this quadruped position can provide an appropriate assessment to determine squat stance.

TRX Deep Squat

The TRX deep squat allows patients to use their upper extremities to partially unload the movement. Plus, it provides the necessary support to prevent compensatory motion. If someone can’t fully resolve their ankle DF or hip flexion, the TRX can allow them to work around this impairment by shifting the COM posteriorly.

Heels Elevated Squat (COM/BOS Modification)

This progresses from the TRX by removing the UE support and loading the movement pattern. However, the elevated heels does not only mean that you have adjusted for ankle mobility deficits. There’s much more biomechanically going on (e.g. joint alignment, anterior chain stability requirements, posterior chain mobility requirements, etc).

This exercise provides is a posterior shift of the COM in relation to the base of support (BOS). Modifying the COM/BOS orientation causes a cascade of changes that alters the global movement pattern, not just the ankles.

Progressive Box Squats

The Box Squat is one of the more common squat variations I use to train the squat pattern. It allows beginners and those with non-optimal mobility to squat without having to control their COM in the difficult transition phase (eccentric to concentric). It is also a great way to teach the squat from the bottom up.

Goblet Squat

The Goblet Squat is my favorite squat exercise; both for movement pattern work and for loading. Adding a load into the system helps to create more tension in the body, which can aid in stabilization. The act of holding the weight anterior of your COM allows for ease with posterior weight shift during the squat. And the proper Goblet Squat form ensures that there will be no valgus collapse because your elbows will be in the way.

Front Squat

The Front Squat and Back Squat are exercises for intermediate/advanced strength and performance training. These are highly technical lifts that require a great deal of strength, mobility, and skill.

Specifically, the front squat requires a great deal of ankle dorsiflexion to perform without compensations. But it is a great way to start loading up the squat that doesn’t involve too much trunk flexion.

Back Squat

The deep back squat is difficult to perform well. I see many people hacking this one up at the gym by performing some weird type of box squat romanian deadlift hybrid where they end up lifting most of the weight with their back. This occurs either because of poor technique, impaired ankle mobility, and/or the inability to get into their hips. Regardless, if someone’s back is sore after they back squat, you may want to consider regressing them to the front squat or goblet squat.

For more information on the front and back squat, check the references below.

Bottom Line

In the end, it’s just important to realize that everyone is different. No one will have the exact same squat. Some will easily be able to drop all the way down, some will only make it to a little below parallel. Some people may need a lot of mobility work, some may need a lot of stability work. And everyone will have different kinematic motion. Therefore, everyone will require a different training progression, different cues, and different “parts” work.

For some, it is not a realistic goal or one worth chasing. For others, it’s a great opportunity to improve movement and performance.

The key is to respect people’s individuality, don’t force it, and respect that it may take a long time for the tissues to adapt to the specific demands of a deep squat.

Dig Deeper

Kjaer, M. “Role of Extracellular Matrix in Adaptation of Tendon and Skeletal Muscle to Mechanical Loading.” Physiological Reviews 84.2 (2004): 649-98

HENNING, C. E., M. A. LYNCH, and K. R. GLICK, Jr. An in vivo strain gage study of elongation of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am. J. Sports Med. 13:22-26, 1985.

Klein K. The deep squat exercise as utilized in weight training for athletes and its effects on the ligaments of the knee. J Assoc Phys Ment Rehabil 15: 6–11, 1961

Escamilla RF. Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 127–141, 2001.

Meyers E. Effect of selected exercise variables on ligament stability and flexibility of the knee. Res Q 42: 411–422, 1971.

Chandler T, Wilson G, and Stone M. The effect of the squat exercise on knee stability. Med Sci Sports Exerc 21: 299–303, 1989.

Bloomquist, K., H. Langberg, S. Karlsen, S. Madsgaard, M. Boesen, and T. Raastad. “Effect of Range of Motion in Heavy Load Squatting on Muscle and Tendon Adaptations.” European Journal of Applied Physiology 113.8 (2013): 2133-142.

Hartmann, Hagen, Klaus Wirth, and Markus Klusemann. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine 43.10 (2013): 993-1008.

Caterisano A, Moss RF, Pellinger TK, Woodruff K, Lewis VC, Booth W, Khadra T. The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 Aug;16(3):428-32.

Steiner M, Grana W, Chilag K, and Schelberg-Karnes E. The effect of exercise on anterior-posterior knee laxity. Am J Sports Med 14: 24–29, 1986.

Esformes, Joseph I., and Theodoros M. Bampouras. “Effect of Back Squat Depth on Lower-Body Postactivation Potentiation.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27.11 (2013): 2997-3000.

Salem, George J. et al. Patellofemoral joint kinetics during squatting in collegiate women athletes. Clinical Biomechanics 16:424-430, 2001.

Bryanton, Megan A., Michael D. Kennedy, Jason P. Carey, and Loren Z.f. Chiu. “Effect of Squat Depth and Barbell Load on Relative Muscular Effort in Squatting.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research26.10 (2012): 2820-828.

Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res 24: 3497–3506, 2010

Escamilla, RF, Fleisig, GS, Zheng, N, Lander, JE, Barrentine, SW, Andrews, JR, Bergemann, BW, and Moorman, CT. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 1552–1566, 2001a.

Walter, Chip. Last Ape Standing: The Seven-million Year Story of How and Why We Survived. New York: Walker &, 2013

Lieberman, Daniel. The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease. New York: Pantheon, 2013. Print

Cook, Gray. Movement: Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, and Corrective Strategies. Aptos, CA: On Target Publications, 2010. Print.

Dan John (Here)

T-Nation – Squat Articles (many great articles here)

Westside Barbell – Squat Articles

DeepSquater Articles

Bret Contreras (Here)

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий