https://squatuniversity.com/2016/01/22/debunking-squat-myths-are-deep-squats-bad-for-the-knees/

by

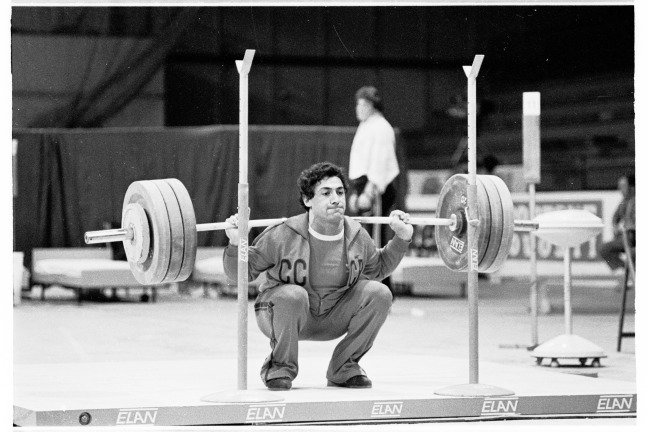

The squat is a staple exercise in almost every resistance-training program. Today athletes of all ages and skill levels use the barbell squat to gain strength and power. However, a good amount of controversy still exists on its safety. There are many opinions when it comes to optimal squat depth. Some experts claim squatting as deep as possible (ass-to-grass) is the only way to perform the lift. Others believe deep squats are harmful to the knees and should never be performed. So who should we believe?

History 101

To start, we need to discuss where the fear of deep squatting originated. Let’s take a trip back to the 1950’s. We can trace the safety concerns with the deep squat back to a man by the name of Dr. Karl Klein. The goal at the time was to understand the reason behind the rise in number of college football players sustaining serious knee injuries. He suspected these injuries were in part due to the use of full range of motion deep squats during team weight training. Klein used a crude self-made instrument to analyze the knees of several weightlifters who frequently performed deep squats.

In 1961 he release his findings, stating that deep squatting stretched out the ligaments of the knee (1). He claimed this was evidence that athletes who performed the deep squat were potentially compromising the stability of their knees and setting themselves up for injury. He went on to recommend that all squats be performed only to parallel depth.

Klein’s theory was eventually picked up in a 1962 issue of Sports Illustrated. This was the catalyst he needed to spread the fear of deep squatting and save the knees of athletes everywhere. The American Medical Association (AMA) soon after came out with a position statement cautioning against the use of deep squats (2). The Marine Crops eliminated the “squat jumper” exercise from their physical conditioning programs (2). Even the superintendant for New York schools issued a statement banning gym teachers from using the full depth squat in physical education classes (2).

There were some individuals who disagreed with Dr. Klein. In May of 1964 Dr. John Pulskamp (a regular column in the notorious Strength and Health) wrote, “full squats are not bad for the knees and they should certainly not be omitted out of fear of knee injury” (5). Despite Dr. Pulskamp’s best efforts, the damage that Klein inflicted had been done. By the end of the decade strength coaches across the country stopped teaching the full depth squat. In some cases, the squat was dropped from training programs all together (1).

Thanks to the advancement in exercise science and biomechanics research, we have learned so much more about forces sustained during squats. Lets now go over what we have learned in the past few decades in order to better understand what exactly happens at the knee joint during the deep squat.

Squatology 101

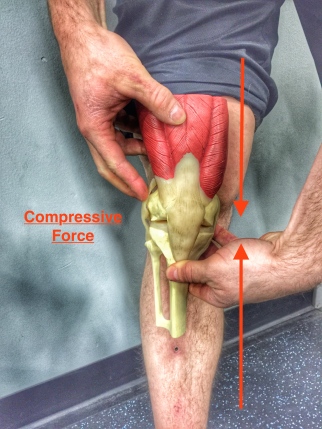

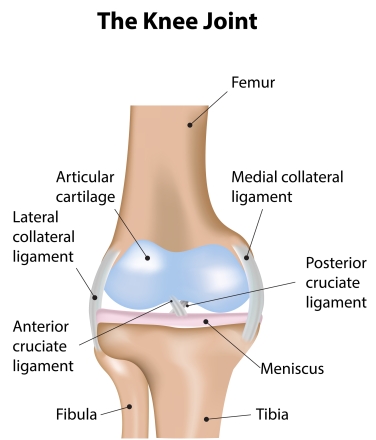

When we squat our knee sustains two types of forces: shear and compressive. Shear forces are measured by how much the bones in our knee (femur and tibia) want to slide over each other in the opposite directions. These forces in high levels can be harmful to the ligaments inside the knee (ACL and PCL). These small ligaments are some of the primary structures that hold our knee together and limit excessive forward & backward movement.

Compressive force is the amount of pressure from two parts of the body pushing on each other. There are two different areas that sustain this type of force in the knee. The meniscus absorbs the opposing stress between the tibia and the femur. The second type of compressive force is found between the backside of the patella (knee cap) and the femur. As the knee bends during the squat, the patella comes in contact with the femur. The deeper the squat, the more connection between the patella and the femur.

When we look at these forces (shear and compression) we see that they are typically inversely related. This means when the knee flexes during the squat, compressive forces increase while shear forces decrease (6).

Ligament Safety

Some medical authorities have cautioned against the use of deep squats due to excessive strain placed on the ligaments. However, it appears these concerns are not based in science at all.

Science now tells us that the ligaments inside our knee are actually placed under very little stress in the bottom of a deep squat. The ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is the most well known ligament of the knee. ACL injuries are common in popular American sports such as football, basketball, soccer, lacrosse, etc. The stress to the ACL during a squat is actually highest during the first 4 inches of the squat descent (when the knee is bent around 15-30°) (7). As depth increases the forces placed on the ACL significantly decrease. In fact, the highest forces ever measured on the ACL during a squat has only been found to be around 25% of its ultimate strength (the force needed to tear the ligament) (8).

The PCL (posterior cruciate ligament) is the second ligament that is found inside the knee. During the squat it sustains max forces just above a parallel squat position (around 90° of knee flexion) (10). Just like the ACL, this ligament is never placed under excessive stress during the squat. The highest recorded forces on this ligament have been only 50% of the estimated strength in a young athlete’s PCL (10).

In fact, science has shown that the deeper you squat the safer it is on the ligaments of your knee. Harmful shear forces are dramatically decreased due to an increase in compression. Also, the muscles in our legs work together to stabilize the knee. As we squat the hamstrings work with the quadriceps to counteract and limit excessive movement deep inside the knee (6).

Thus, the ACL and PCL stay unharmed no matter how deep the squat!

Knee Stability

The original studies by Dr. Klein claimed squatting deep stretched out the ligaments that hold the knee together and ultimately leaving it unstable. However, these claims have never been replicated. Researchers have even used a copy of Klein’s testing instrument in their own studies. Their findings disapproved Klein’s research. They found that athletes who used the deep squat had no difference in the laxity of their knee ligaments than those who only squatted to parallel (3).

Science has actually shown that squatting deep may have a protective effect on our knees by increasing its stability! In 1986 researchers compared knee stability among powerlifters, basketball players, and runners. After a heavy squat workout the powerlifters actually had more stable knees than the basketball players (who just practiced for over an hour) and runners (who just ran 10km) (9). In 1989 another group of researchers were able to show that competitive weightlifters and powerlifters had knee ligaments that were less lax than those who never squatted (4). Again and again, research has shown that the deep squat is a safe exercise to include in a healthy athlete’s training program.

When can deep squatting be harmful?

Theoretically, most of the damage that the knees would sustain from deep squats would be due to excessive compression forces. Some authorities claim that because deep squats raise compression forces at the knee they cause the meniscus and the cartilage on the backside of the patella to wear away. While an increase in compression would lead to a greater susceptibility for injury, there has been no such cause-and-effect relationship established by science!

If this were true, we would expect to see extreme amounts of arthritis in the knees of weightlifters and powerlifters. Fortunately, this is not the case. There is little evidence of cartilage wear in the knees as a result of long-term weight training. In fact, elite weightlifters and powerlifters (who sustain loads up to 6x bodyweight to the knee in the bottom of a deep squat) have relatively healthy knees compared to you and me! (11)

Considerations for Squatting Deep

Every coach must consider a few things when determining optimal squat depth for an athlete. Everyone should have the capability to perform a bodyweight squat to full depth, period. That being said, the depth of the barbell squat should be based on the requirements of an athlete’s sport. A weightlifter for example needs to establish strength in the full depth squat in order to lift the most amount of weight on the competition platform. On the other hand, a barbell ass-to-grass squat is not necessary for a soccer player. He or she can still gain efficient strength and power from a parallel depth squat.

An athlete’s injury history also needs to be taken into account when determining optimal squat depth. Often athletes will ignore pain in their pursuit of performance gains. The phrases “no pain, no gain” and “know the difference between hurt and injured” cannot apply to the weight room. Pain is like the warning light in our car. The light is indicating something is wrong. Just as ignoring your car’s warning light on will lead to engine problems, pushing through pain in the weight room will lead to injury of our physical body. For this reason, if an athlete is injured and has knee pain, deep squats may not be the best choice. The depth of the squat must be limited to a pain free range if we want to stay healthy and continue to compete injury free.

Squat depth should also be limited if it cannot be performed with good technique. Poor movement only increases our risk for injury. An athlete’s body is like a finely tuned sports car. Constantly driving pedal to the metal and taking aggressive turns will lead the car to break down faster. The same goes for squatting. You can only lift so much weight poorly for so long before your body sustains an injury. Squatting to full depth poorly is a great way to invite injury.

Take Away

So what have we found out since 1964? Contrary to mainstream belief, we now know that squatting deep or “ass to grass” is actually not as dangerous as Dr. Klein made it out to be. Research again and again has failed to support the theory that deep squats are bad for the knees in healthy athletes.

For athletes with healthy knees, performing the squat to full depth should not cause injury as long as heavy loads are not used excessively. Proper training programs should employ light, medium and heavy intensity cycles throughout the year in order to lessen any harmful effects of constant heavy loading. Now that you have a deeper understanding of full depth squats, feel free to get that ass to the grass!

Until next time,

With

References

- Todd T. Karl klein and the squat. Historical Opinion. NSCA Journal. June-July 1984: 26-67.

- Underwood J. The knee is not for bending. Sports Illustrated. 16: 50, 1962.

- Myers E. Effect of selected exercise variables on ligament stability and flexibility of the knee. Research Quarterly. 1971; 42(4):411-422.

- Chandler T, Wilson G & Stone M. The effect of the squat exercise on knee stability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989; 21:299-303

- Pulskamp, JR. Ask the doctor. Strength and Health. 1964, May. p. 82.

- Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. JSCR. 2010;24(12):3497-3506.

- Li G, Zayontx S, Most E, DeFrante LE, Suggs JF, & Rubash HE. Kinematics of the knee at high flexion angles: an in vitro investigation. J Orthop Res. 2004b; 27:699-706.

- Gullett JC, Tillman MD, Gutierrez GM & Chow JW. A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:284-292

- Steiner ME, Grana WA, Chillag K & Schelberg-Karnes E. The effect of exercise on anterior-posterior knee laxity. Am J Sports Med. 1986; 14:24-29.

- Escamilla RF, Fleisig GF, Zheng N, Lander JE, Barrentine SW et al. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001a; 33:1552-1566.

- Fitzgerald B & McLatachie GR. Degenerative joint disease in weight-lifters fact or fiction. Brit J. Sports Med. 1980 August. 14(2&3):97-101

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий